In the late 17th to mid-18th century there was a boom in the publication of conduct books for women, which instructed on proper manners and moral behaviour. As with modern etiquette guides, the existence of such books hint at the anxieties about the proper way to conduct oneself in social situations. They also provide a valuable insight into the conventions surrounding behaviour, and the expectations of women at that time.

Seventeenth century conduct books were almost entirely written by men for a female readership – and they give strikingly similar advice to their target audience of young aristocratic women. Such books typically contain guidance on religion; how to choose a husband and live with his faults; how to manage a household and raise children; and appropriate behaviour and recreations. This is mixed with censure of faults such as vanity, immodesty, talking and laughing too much, and keeping company with those who might damage their reputation.

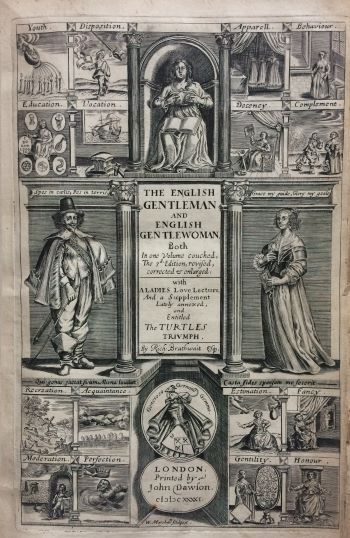

We have two conduct books from this time in Trinity Hall’s libraries. Richard Brathwaite’s The English Gentlewoman, first published in 1631, was one of the first conduct books aimed specifically at women. It is a companion work to The English Gentleman, which was published the previous year – and our edition combines both books into a single volume [1]. In his preface, Brathwaite explains that he is presenting something for ladies to aspire to: ‘I have here presented unto your view one of your own sex one whose improved education will be no blemish but a beauty to her nation’. The frontispiece gives the motto “Grace my guide, Glory my goale” which expresses the conventional ideal of feminine behaviour.

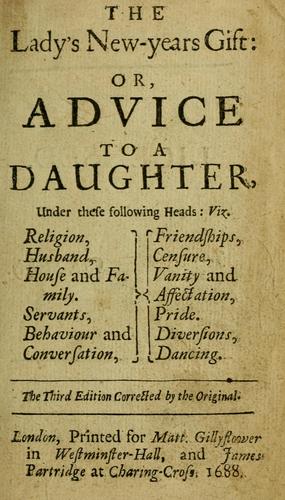

Published more than fifty years after the English Gentlewoman, came George Savile, the Marquis of Halifax’s (1633-1695) The lady’s new-years gift, or, Advice to a daughter [2]. It was written for his daughter Elizabeth (1675-1708) when she was twelve years old. Full of fatherly affection, Halifax gives Elizabeth advice on how to exist within the strictures of society and of marriage. Halifax never intended the book to reach a wide audience. It was circulated privately at first in a few manuscript copies, but before too long it was pirated for publication. And it was incredibly popular, with six editions in the 17th century and dozens of reprints in the 18th century.

So what were the key rules for a lady in the 17th century to follow?

Dress modestly

Women’s vanity and pride was seen as the root of much of their challenging behaviour. Richard Brathwaite devotes considerable space to appearance in The English Gentlewoman, arguing that women should dress modestly.

He condemns brightly coloured fashionable clothing (‘pye-coloured fopperies’ and ‘thinne Cobweb attires’) which ‘detracts from the native beauty of the feature’. He is particularly incensed by women who wear ‘gaudy’ dresses with a low neckline that exposed the breasts, or ridiculous foreign fashions. In his opinion, such dress is against Christian values, and likely to encourage licentious behaviour and sin.

Halifax similarly cautions against vanity: ‘the Fault to which your Sex seemeth to be the most inclined’. In part because it makes the person obnoxiously full of themselves and ridiculous in the eyes of others:

Shee doth not like herself as God-Almighty made her, but wil have some of her own workmanship; which is so farr from makeing her a better thing than a woman, that it turneth her into a worse Creature than a Monkey. (p. 400.)

Be seen and not heard

As well as modest dress, modest speech is a must. In a nutshell, a gentlewoman should be seen and not heard. As Brathwaite declares: ‘It will become her to tip her tongue with silence’. This is part of the all important modest behaviour. There are also certain topics young women should not talk about. As Brathwaite puts it, she should not venture any ‘strange opinions’ on matters of state or religion. As the majority of women were given little education they were unlikely to have had an advantage in such debates.

Halifax also cautions against women being too talkative or amusing: ‘Jollity is as contrary to Wit and Good Manners, as it is to Modesty and Vertue’. A woman drawing too much attention to herself opened herself up to ridicule. The ideal woman has nothing to say.

Don’t have too much fun

Taking part in amusements outside the home brought disapproval, because it risked her spending time in dubious company. And further, for married women, it took her away from her family responsibilities. Brathwaite advises gentlewomen not to frequent ‘stage playes, wakes, solemn Feasts and the like’ where they might come into contact with company that might corrupt them. Instead, he urges women to spend their time at home looking after their family or in religious devotions – the price of having too much pleasure on earth would be paid for in the afterlife with ‘their soules appointed to hell fire’.

Halifax is perhaps more concerned with appearances than with sin. He sees nothing wrong with his daughter making occasional visits to the play house, entertaining company, playing cards, and dancing. As long as it wasn’t so often that it gave her reputation for idleness:

It wil engage you into a habit of idlenesse, and ill howers, draw you into ill mixed company, make you neglect your civilities abroad, and your business at home, and impose into your acquaintance such as wil doe you no credit. (p.405)

Obey your husband

One of the key functions of conduct books was to advise women on how to avoid marital discord. Both Brathwaite and Halifax say that this could be achieved by a woman obeying her husband, and managing his faults through her feminine wiles. If a marriage was unhappy she would have little option than to learn to live with it. Divorce was difficult and costly, and would lead to a woman’s social ostracisation.

The majority of Hallifax’s guide is a manual on how to survive a bad marriage. There are hints that he was concerned to arm his daughter against the inevitable discontents of a life spent in subjection to a husband.

Elizabeth was to marry just four years later, aged sixteen, to Philip Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Chesterfield (1673-1726). Unfortunately, the marriage wasn’t a particularly happy one and correspondence shows that she had to put up with his adultery, drunkenness, and neglect, until her death in 1708. [3]

Use of conduct books

Conduct manuals sought to define every aspect of women’s lives by presenting an ideal of how they should behave. Both Brathwaite and Halifax wrote these books with gentlewomen (not women in general) as their target audience. Unsurprisingly, the books uphold the 17th century ideal of women: as modest, restrained and subservient to her husband. To modern eyes, however, nothing could be more virtuous, restrained or dull than the lady they describe!

What might a gentlewoman have thought if she had been given this book? Was she grateful for the advice, and viewed it as a model to aspire to? Did she laugh at its precepts? Did she read it at all? These questions will have to remain unanswered.

References

[1] Brathwaite. The English Gentleman; and the English Gentlevvoman : Both in One Volume. The Third Edition Revised, Corrected, and Enlarged. ed. London: Printed by Iohn Dawson, 1641. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A16659.0001.001

[2] Halifax, George Savile. Advice to a Daughter. Aberdeen: Printed for and by Francis Douglass and William Murray, 1753. Online at: http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A44704.0001.001

[3] Savile, G. (1989). The works of George Savile, marquis of Halifax. (Vol. 2). M. N. Brown (Ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (2013), pp. 361-2. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780198123378.book.1