Meet the Trinity Hall community

The people of Trinity Hall are the heart of our College. Our students supporting their peers across the College, University and wider community; our young apprentice staff members learning their trade; our Fellows conducting groundbreaking research.

Here we meet just a few of the wonderful people that make Trinity Hall what it is.

You can also hear from current students about their course and experience at Trinity Hall.

Meet Ryan Ko: our Varsity Water Polo champion

Find out more

Head Gardener celebrates 10 years of service to the Trinity Hall Gardens

Find out more

Meet Lucia Laffan: altering the way we look at fashion

Find out more

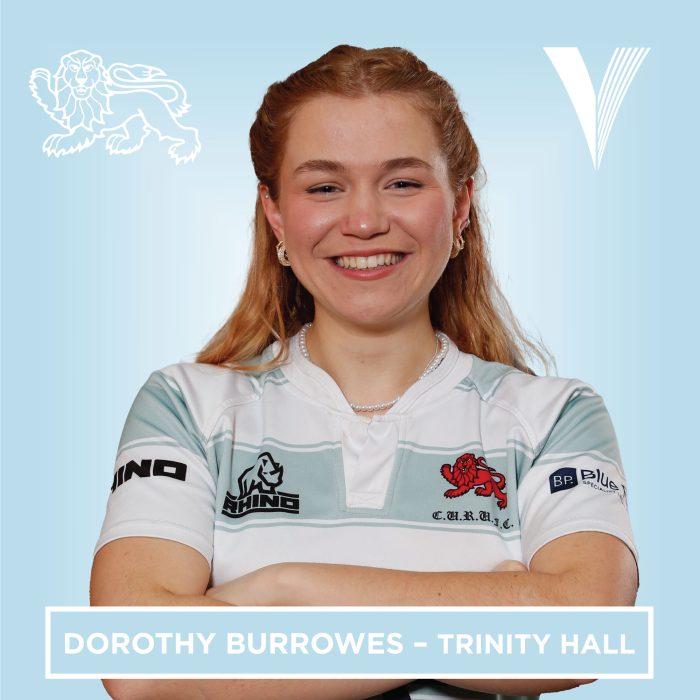

Meet our newest Varsity Rugby star

Find out more

Vladimir Kara-Murza welcomed back to Trinity Hall

Find out more

Changing the future of cancer care

Find out more

History students’ outstanding work recognised

Find out more

Fellow shortlisted for Women in Technology Award

Find out more

Advice from our sports societies

Find out more

Augmented reality, cobots, sunken mines and start-ups

Find out more

Society Focus: Trinity Hall Chapel Choir

Find out more

Society Focus: Introducing the Geography Society

Find out more

Society Focus: Introducing the Squash Club

Find out more

Society Focus: Introducing the Climbing Club

Find out more

Society Focus: Introducing the Philosophy Society

Find out more

Society Focus: Introducing Trinity Hall Netball

Find out more

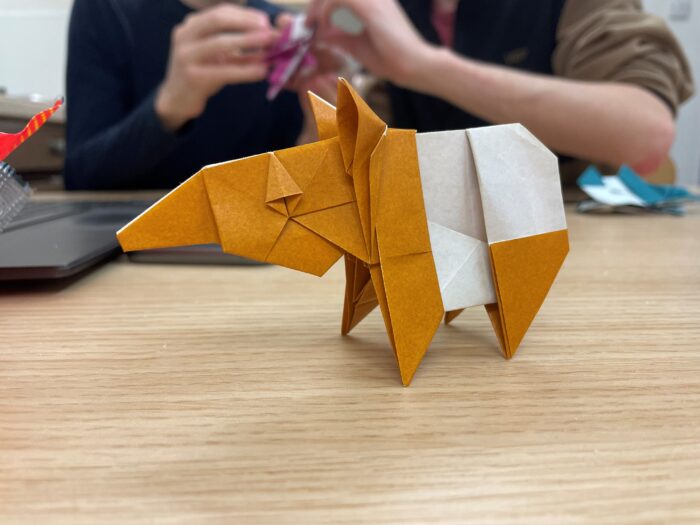

Society Focus: Introducing the Trinity Hall Origami Society

Find out more

Society Focus: Introducing the Trinity Hall Music Society

Find out more

Society Focus: The Trinity Hall Cold Water Swimming Society (Orcas)

Find out more

Meet the New Deputy Head Porter, Paul Clare

Find out more

Meet Russell Waller, Head of Buildings and Services

Find out more

Meet Irina Atkinson: our new tutorial administrator and former Trinity Hall porter

Find out more

Dorothy Burrowes

Find out more

Meet Jordi Ferrer Orri who uses microscopes to help fight climate change

Find out more

Karen Paul – A lawyer’s love for theatre

Find out more

The bedmaker who writes crime fiction

Find out more

Jam Greenland

Find out more

Alumni Officer celebrates 20th anniversary at Trinity Hall

Find out more

Captain of the oldest Football Club in the world

Find out more

Levonne De Freitas, Manciple

Find out more

New Head of Housekeeping reflects on almost 20 years at Trinity Hall

Find out more

Abisola Omotayo, alumna

Find out more

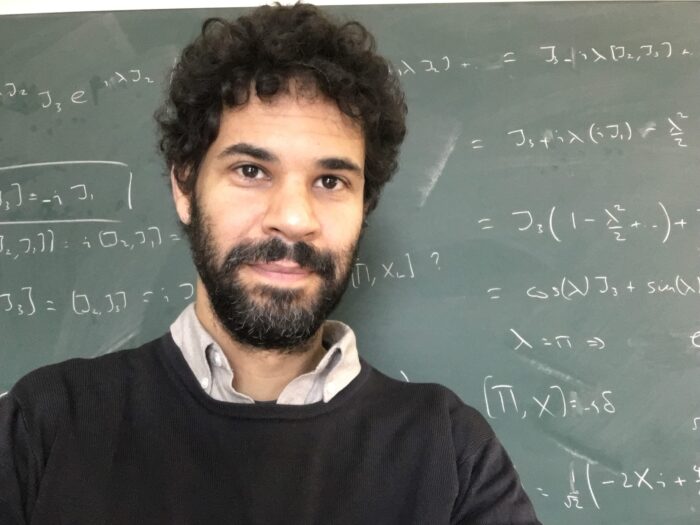

Dr Ron Reid-Edwards, Fellow in Mathematics

Find out more

Diekara Oloruntoba-Oju, alumna

Find out more